Clang/LLVM overview

Compilers are complex programs with complex requirements. The two most widespread C compilers, GCC and Clang/LLVM, are 10–15 million lines of code behemoths, designed to produce optimal machine code for whatever arbitrary target the user desires. In this blog post I’m going to give an overview of how the Clang/LLVM C compiler works; from processing the source code to writing native binaries.

First of all, what is a compiler?

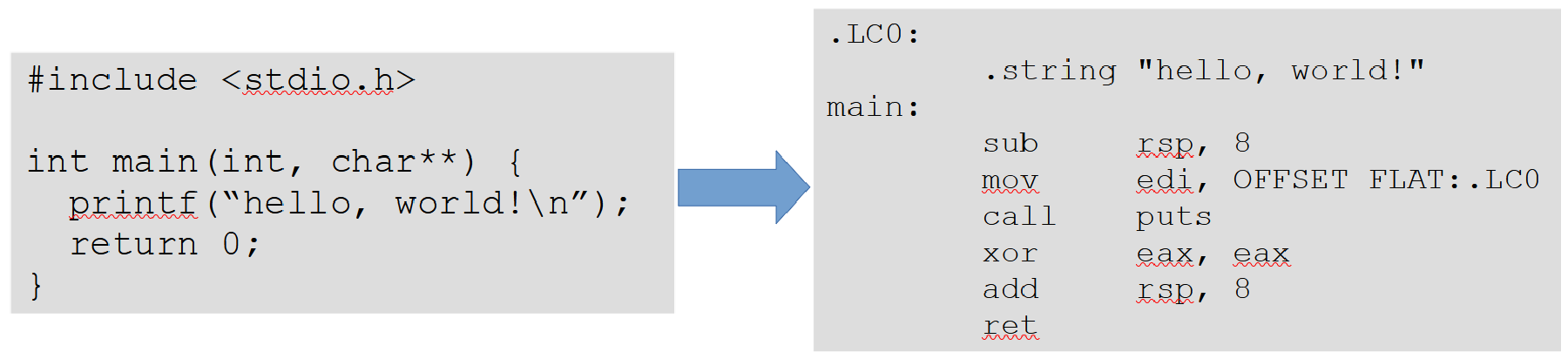

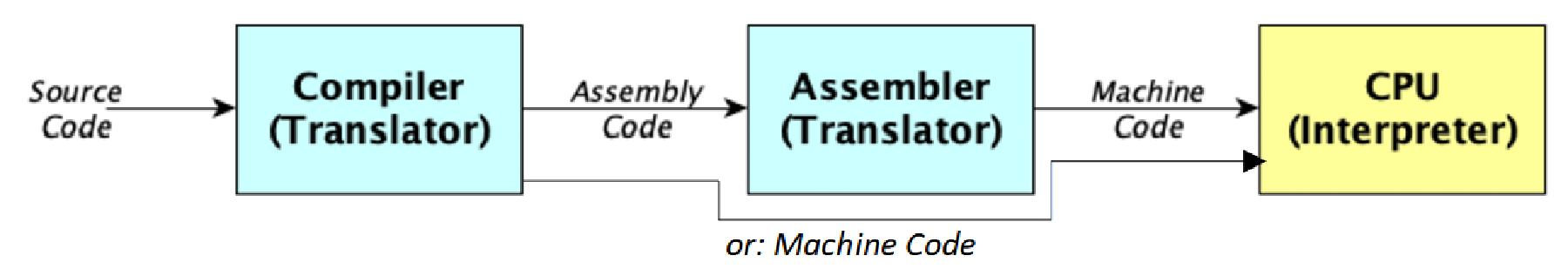

A computer (or CPU, rather) executes binary machine code. The human-readable form of machine code is called assembly code. However, assembly code is very low-level and very unnatural to write for humans. So we write our programs in higher-level programming languages like C, C++, Rust, etc. instead and let a compiler translate that source code into machine code.1

There are many more compilers than GCC and Clang, for a wide variety of programming languages.

One can distinguish between two kinds of compilers:

- AOT (ahead-of-time) compilers. These are compilers where all of the source code is compiled to target code before the program is run. Basically, every C/C++ compiler is an AOT compiler for example.

- JIT (just-in-time) compilers. JIT compilers compile code even while the program is running. Examples: Chromium’s JavaScript engine, Dart, LuaJIT

At first, this sounds like JIT is a lot slower than AOT compilation but that’s not necessarily true. JIT compilers have more information about the machine/CPU they’re targetting and can take that into account when compiling. AOT compilers, on the other hand, mostly produce code for the “lowest common denominator”2, if you don’t explicitly tell it for what target it should tune the code. So even if you have the very latest Intel 12th generation CPU with the very latest feature set, your compiler will not make use of those features when targetting “just any x86-64 machine”.

Additionally, JIT compilers have more information about the runtime behaviour of the program. For example, if the JIT compilers sees “oh, this function is only called with an integer argument greater than 128”, it can use that to optimize the function. An AOT compiler can deduce some information too, but in most cases that information is just very hard to find out without running the program.3

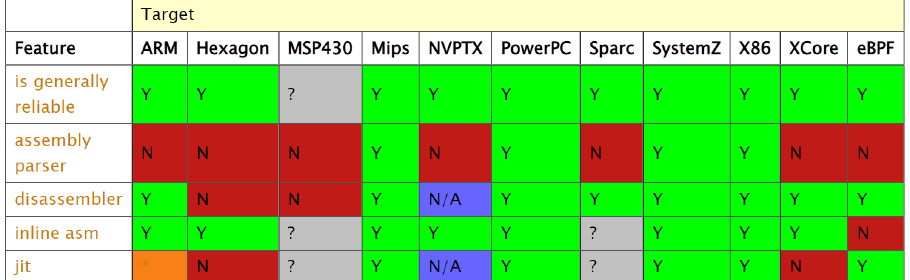

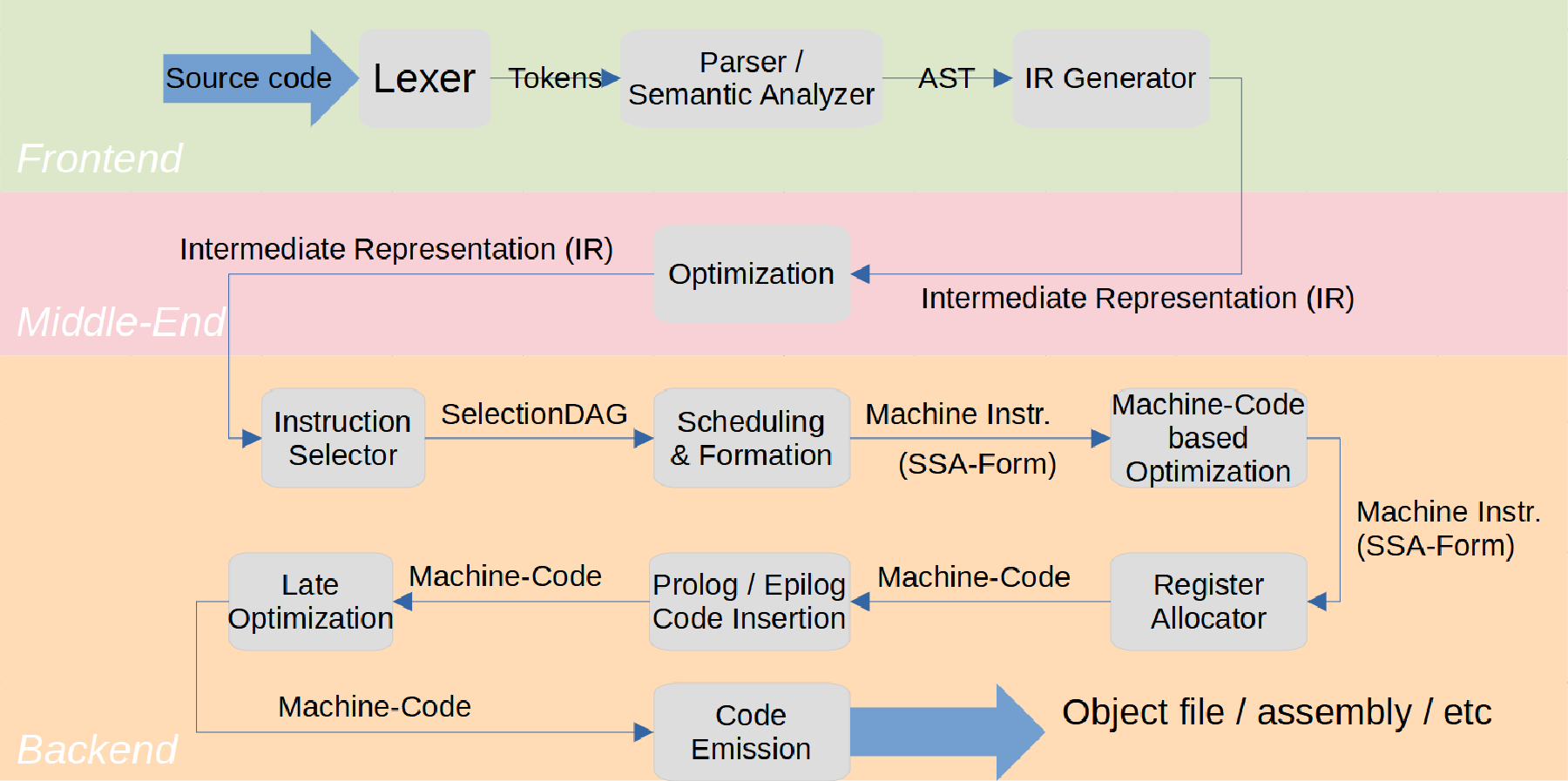

As you can see in the above picture, there’s roughly 3 phases of compilation:

- Frontend

- In this step, all the source code is processed and an intermediate representation (IR) is generated.

- In our case,

Clangis the frontend andLLVMis the middle- and backend. - There are many LLVM frontends for many programming languages, Clang is just the one for C/C++.

- Middle-end

- The middle-end is one of the great features of LLVM. In this phase, the IR is optimized. Overall, most of the optimizations are done here. The cool thing is that LLVM IR is completely universal; all frontends produce IR and all backends consume IR. That way, if you write an optimization pass for the middle end, it’ll work for many languages and many target CPUs.

- Backend

- The backend will now consume the optimized IR and produce machine code, which (after linking) can be executed on the target machine. The backend will also apply some machine specific optimization passes.

I’ll now go a bit more into detail about how these 3 parts work.

The first thing the frontend does is read the source code character by character and produce so-called tokens.

For example, for the following C source code:

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

printf("hello, world!\n");

return 0;

}

The list of tokens could look like this:

int,

identifier(“main”),

lparen,

int,

identifier(“argc”),

comma,

// and so on ...

Additionally, each token will also have its source location (that is, its file, line and column) associated with it.

In this phase, you basically get rid of all whitespace, comments, and transform the source code into something that can more easily be processed to produce the the abstract syntax tree (AST) and, following that, the IR.

The lexer only does very simple recognition of the basic syntactical building blocks of the source code.

For example, if you forget the terminating " of a string, the lexer will complain; but not if you use a wrong type or an undefined symbol.

Using the list of tokens from the previous step, we’re now constructing a tree. And not just any tree, we’re constructing a so-called abstract syntax tree (AST).

Basically, we’re now recognizing the language structures of the programming language, like definitions, declarations, control flow statements, expressions, type casts, etc.

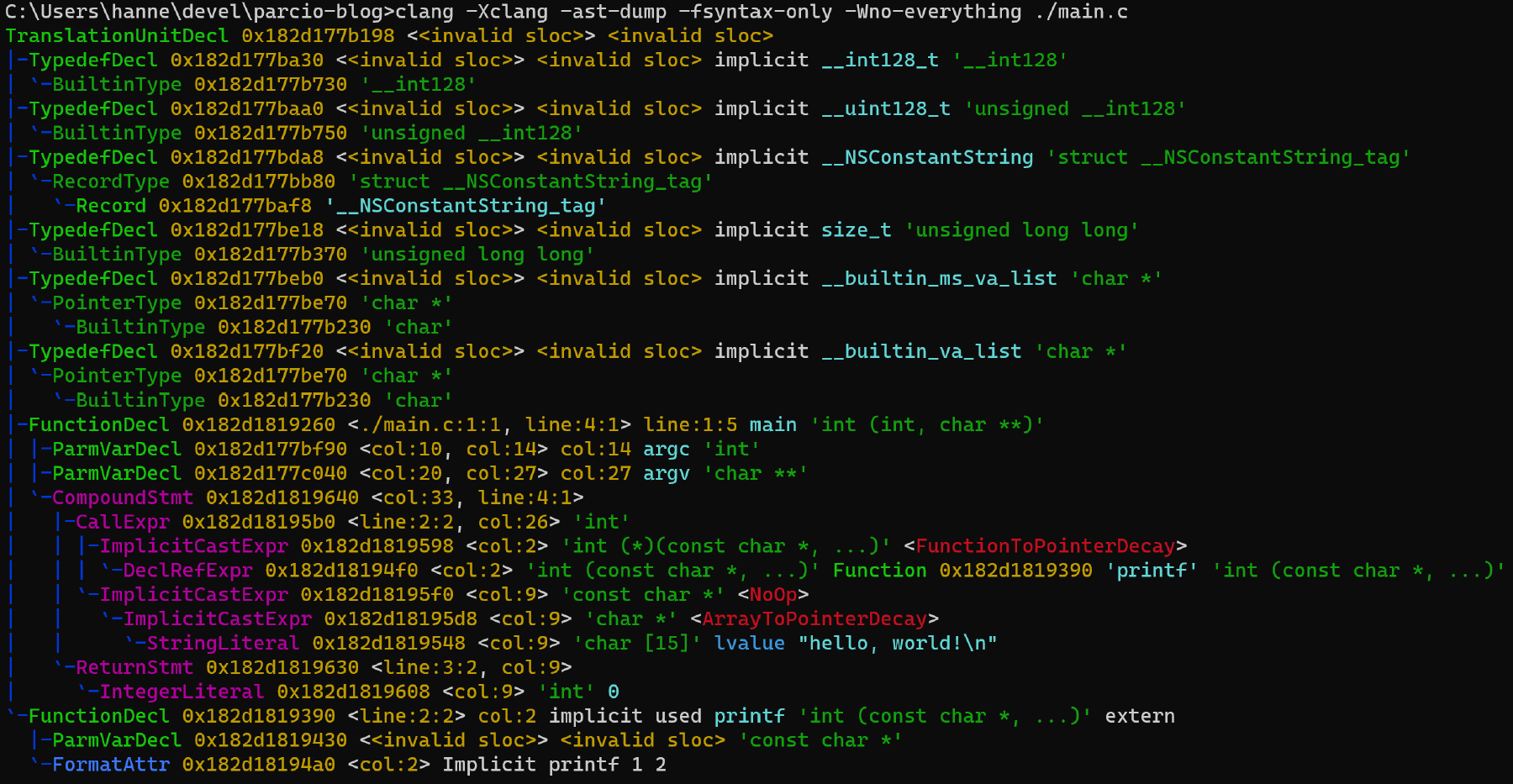

The above image shows the AST for the example C program in 3.1.

<invalid sloc> means invalid source location.

The nodes with <invalid sloc> are “imaginary”, they don’t have any corresponding source location and were added by Clang after the fact.

In the AST, we can clearly recognize the structure of the hello world program above by looking at the nodes with valid source locations:

- The function declaration

int main(int, char **)and the names of the two arguments,argc&argv(FunctionDeclandParmVarDecl) - The compound statement

{ ... }afterwards (CompoundStmt) - The call to

printfwith some implicit casts (CallExpr) - Finally, the

return 0(ReturnStmt)

The parser has some predefined rules, like function-declaration = type identifier ( parameter-list ) ....

It tries to match those rules against the tokens and that way Clang will build the AST.

However, in practice it’s not that easy.

For example, in C there are two ways you can parse a * b.

- Either

aandbare variables and that expression is a multiplication, - or

ais a type name, anda * bis the declaration of a variablebwith typea*(pointer toa)

So to be able to parse this correctly, you need to know beforehand if a is a type or a variable.

In C++ it’s even more complicated.

There’s a saying that “parsing C is hard and parsing C++ is impossible.” The C++ grammar is ambiguous, C++ templates are turing complete and parsing it is literally undecidable.

That’s one of the reasons why Clang has hand-written parsers for both C and C++.

The parser works very closely together with the semantic analyzer (sema). The sema will do things like inferring types, adding type casts, doing validity checks or throwing warnings. For example, warnings about unused code or infinite self-recursion will be thrown by the sema.

The IR generator will now (surprise!) generate rough, unoptimized IR using the AST from the previous step.

LLVM IR is a full-fledged language with well-defined semantics. The IR below was generated for the hello world program from Section 3.1. However, I’d say its workings are a bit out of scope for this blog post, so I’m not going to go into detail here.

@.str = private unnamed_addr constant [15 x i8] c"hello, world!\0A\00", align 1

define dso_local i32 @main(i32 %0, i8** %1) #0 !dbg !8 {

%3 = alloca i32, align 4

%4 = alloca i32, align 4

%5 = alloca i8**, align 8

store i32 0, i32* %3, align 4

store i32 %0, i32* %4, align 4

call void @llvm.dbg.declare(metadata i32* %4, metadata !17, metadata !DIExpression()), !dbg !18

store i8** %1, i8*** %5, align 8

call void @llvm.dbg.declare(metadata i8*** %5, metadata !19, metadata !DIExpression()), !dbg !20

%6 = call i32 (i8*, ...) @printf(i8* getelementptr inbounds ([15 x i8], [15 x i8]* @.str, i64 0, i64 0)), !dbg !21

ret i32 0, !dbg !22

}

declare void @llvm.dbg.declare(metadata, metadata, metadata) #1

declare dso_local i32 @printf(i8*, ...) #2

attributes #0 = { noinline nounwind optnone uwtable "frame-pointer"="all" "min-legal-vector-width"="0" "no-trapping-math"="true" "stack-protector-buffer-size"="8" "target-cpu"="x86-64" "target-features"="+cx8,+fxsr,+mmx,+sse,+sse2,+x87" "tune-cpu"="generic" }

attributes #1 = { nofree nosync nounwind readnone speculatable willreturn }

attributes #2 = { "frame-pointer"="all" "no-trapping-math"="true" "stack-protector-buffer-size"="8" "target-cpu"="x86-64" "target-features"="+cx8,+fxsr,+mmx,+sse,+sse2,+x87" "tune-cpu"="generic" }

Now that we have the IR, we can optimize it. What does “optimizing” even mean, though? When we optimize a program, we want to make it faster or smaller.

Making it run faster is the usual goal that’s achievable for example by combining operations, reducing function calls, resolving recursions, etc. Making the finished program binaries smaller is often done in embedded environments, where you don’t have too much space available.

A single “step” of optimization is called an optimization pass.

Usually when employing optimizations, you’ll bundle a bunch of these together in a chain.

The order is important too: Some optimization passes rely on the fact that some other optimization pass has run before them (that maybe annotated the IR with some analysis information), others produce better results when some other optimization pass has run before them.

But that’s mostly opaque to the user, Clang will do the right thing for you when you just use the -O... commandline argument.

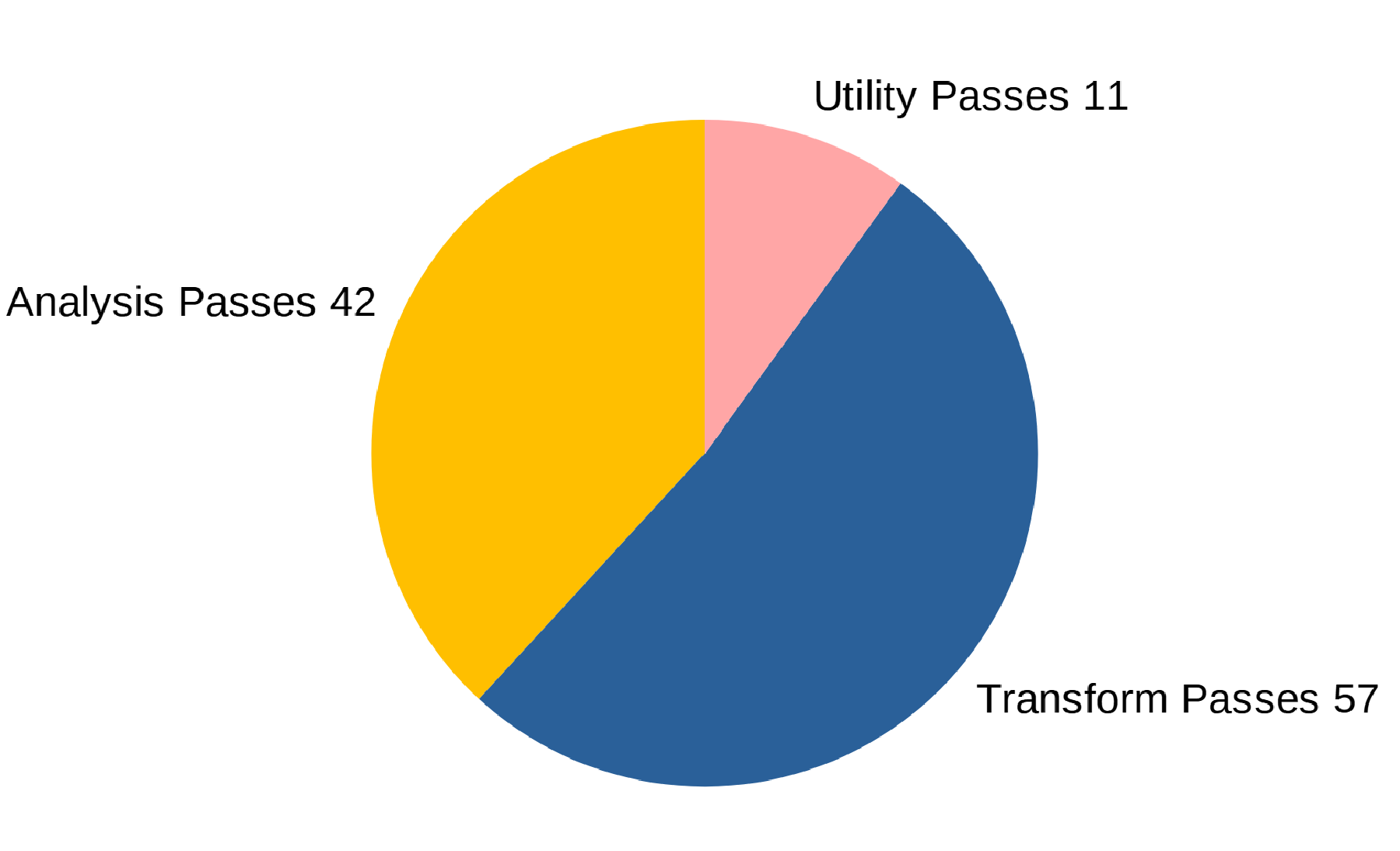

There are three kinds of optimization passes:

- Analysis passes

- Those analyze the IR and try to deduce some information that’s useful (or required) for other optimization passes.

- For example, one analysis pass will deduce information about the call graph, another will find memory dependencies, etc.

- Transform passes

- Transform passes are what actually optimizes the IR. They use the information from the analysis passes to transform the IR in such a way that it’s either faster or smaller afterwards.

- There

-inlinetransform pass will do function inlining (more on that later),-adcewill eliminate dead code,-instcombinecombines redundant instructions, etc.

- Utility passes

- These are mostly used for debugging purposes. These aren’t applied by Clang by default, only if you explicitly tell it to.

- For example, the

-view-cfgpass will use Graphviz to visualize the control flow graph.

To use these optimizations, you can just use the -O... commandline argument for Clang.

For example:

# no optimizations at all (default)

$ clang -O0 main.c

# optimize for speed

$ clang -O1 main.c

# optimize even more for speed

$ clang -O2 main.c

# optimize even more more for speed

$ clang -O3 main.c

# optimize for fastest speed possible

$ clang -Ofast main.c

# optimize for size (basically -O2 with some optimizations that reduce size)

$ clang -Os main.c

# optimize even more for size

$ clang -Oz main.c

As a developer, usually you want your programs to run fast.

So why don’t we always use -Ofast?

- The first reason is that it breaks strict standards compliance.

-Ofastis basically-O3with-ffast-math. Fast-math will do a lot of things that are not compatible with the C or C++ standards. For example, it’ll replace some operation that divides by a floating-point constanta / 0.123by a multiplication with the reciprocal (a * (1 / 0.123)) since multiplication is usually faster, some floating point errors won’t be reported anymore, some things are less accurate, etc. - For large projects, it’ll increase compile time. In many cases, it might still be worth it, but others may not want to do that.

- It might increase program binary size.

Okay, so the problem with -Ofast is mainly non-compliant math.

So why don’t we just always use -O3?

Why is there a -O2 then?

It turns out that’s a pretty good question.

-O3 is basically the same as -O2.

In the LLVM I tested, -O3 enables two more optimization passes than -O2 and for one of them it says in the code “FIXME: It isn’t at all clear why this should be limited to -O3”.

Okay, now that we have optimized the IR, we can go on to the next step:

This is the first phase of the backend. Everything (well, most) target-specific stuff happens here. Now, we want to transform the optimized IR into something that’ll run on the target CPU, and as the first step we’re going to select the instructions for that.

LLVM has multiple instruction selectors:

- SelectionDAG (produces the best results, best documented)

- FastIsel (produces poor results, but runs quickly)

- GlobalIsel (WIP, designed to combine the compilation speed of FastIsel with the quality of SelectionDAG)

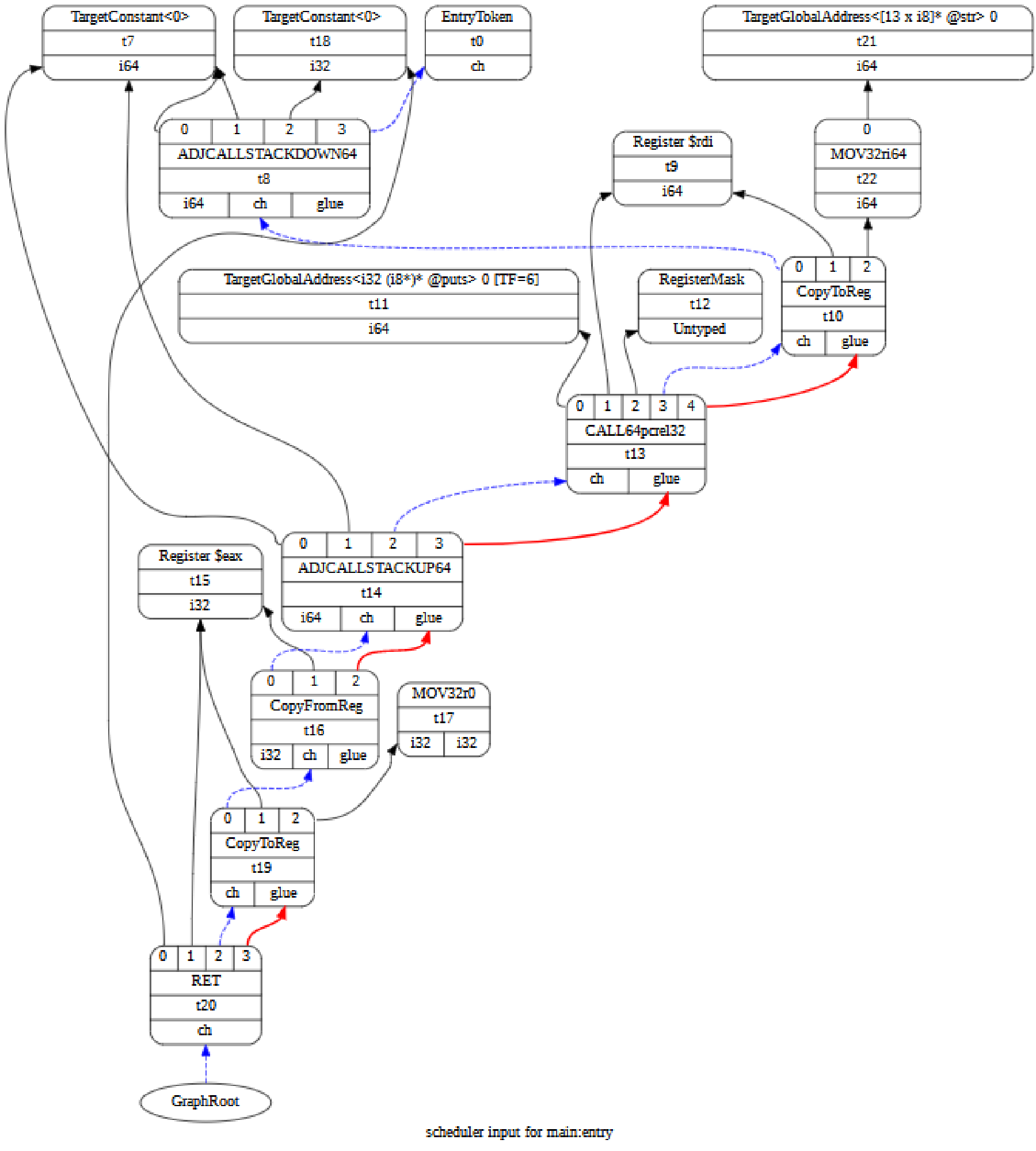

Since SelectionDAG is best documented and produces the best results, I’m going to use that as an example. Actually, SelectionDAG is not only the name of this instruction selector but also the output of it. That is, the output of this instruction selector is called SelectionDAG (selection directed, acyclic graph) too. In this graph, each node is an instruction and the edges are data or control dependencies.4

A finished DAG (for the program from 3.1) looks like this:

But how is that graph built? There are multiple steps involved here:

-

First of all, we’re using static mappings from IR instruction to SelectionDAG node, and the control and dataflow dependencies we can infer from the IR to build an initial, naive SelectionDAG.5

-

Now we’re applying some basic optimizations to it.

-

The (still naive) SelectionDAG we now have might not even be runnable on the target CPU. Maybe it contains operations that aren’t supported or some type doesn’t work with the operation used, etc. In other words, it might be an illegal SelectionDAG. So now, as the first step of making it a legal graph, we’re going the legalize the types. There are two kinds of modifications we can make to the types here:

- Type promotion (converting a small type to a larger one)

- Type expansion (splitting up a larger type into multiple smaller ones)

For example: If the target doesn’t support 16-bit integers, we’re just going to promote it to a 32-bit integer instead. Likewise, if it doesn’t support 64-bit integers, we’re just going to expand it to two 32-bit ints instead.

-

Now, we optimize that again, mostly to get rid of redundant operations introduced by type promotion/expansion.

-

After that, we’re going to legalize the operations. Targets sometimes have weird, arbitrary constraints for the types that can be used for some operations. (x86 does not support byte-conditional moves, PowerPC does not support sign-extending loads from a 16-bit memory location.) So we’ll apply type promotion and type expansion or some custom, target-specific modifications here to make the SelectionDAG legal.

-

Optimize again.

-

Actually select the instructions. This phase is a bit more complicated, but in a nutshell, LLVM will take the instructions in the SelectionDAG we have (which are target-independent instructions that just happen to be executable on the target machine) and translate them into target-specific instructions, while also using pattern-matching to combine instructions where possible.

Now we have a SelectionDAG of machine instructions.

However, CPUs don’t run DAGs.

So we need to linearize the SelectionDAG, that is, form it into a list.

There are many ways to do that, LLVM will just use some heuristics so we, for instance, always have enough registers available, you can also take into account instruction latencies, etc.

You can print the linearized SelectionDAG for some LLVM IR using llc -print-machineinstrs ....

After this, there’s a machine code (actually MIR) based optimization phase.

Up until this point, even if you might not have realized, we acted like the target machine has an infinite amount of one-time assignable registers.

In other words, the IR and SelectionDAG was in the so-called SSA (single static assignment) form. The SSA form simplifies many analyses of the control flow graph of the IR. At this point, we want to select the actual target registers we will use for the previously virtual SSA registers. Most targets only have 16, maybe 32 registers and many of those are reserved for special purposes. It’s possible we don’t have enough physical registers to accomodate all the virtual registers. That means we have to put some of them into main memory instead, which is called spilling.

Now that we’ve selected the physical registers, we’re adding some prologue and epilogue instructions to the function, that is, push some registers on the stack and pop them again later.

After that comes a machine code based optimization phase.

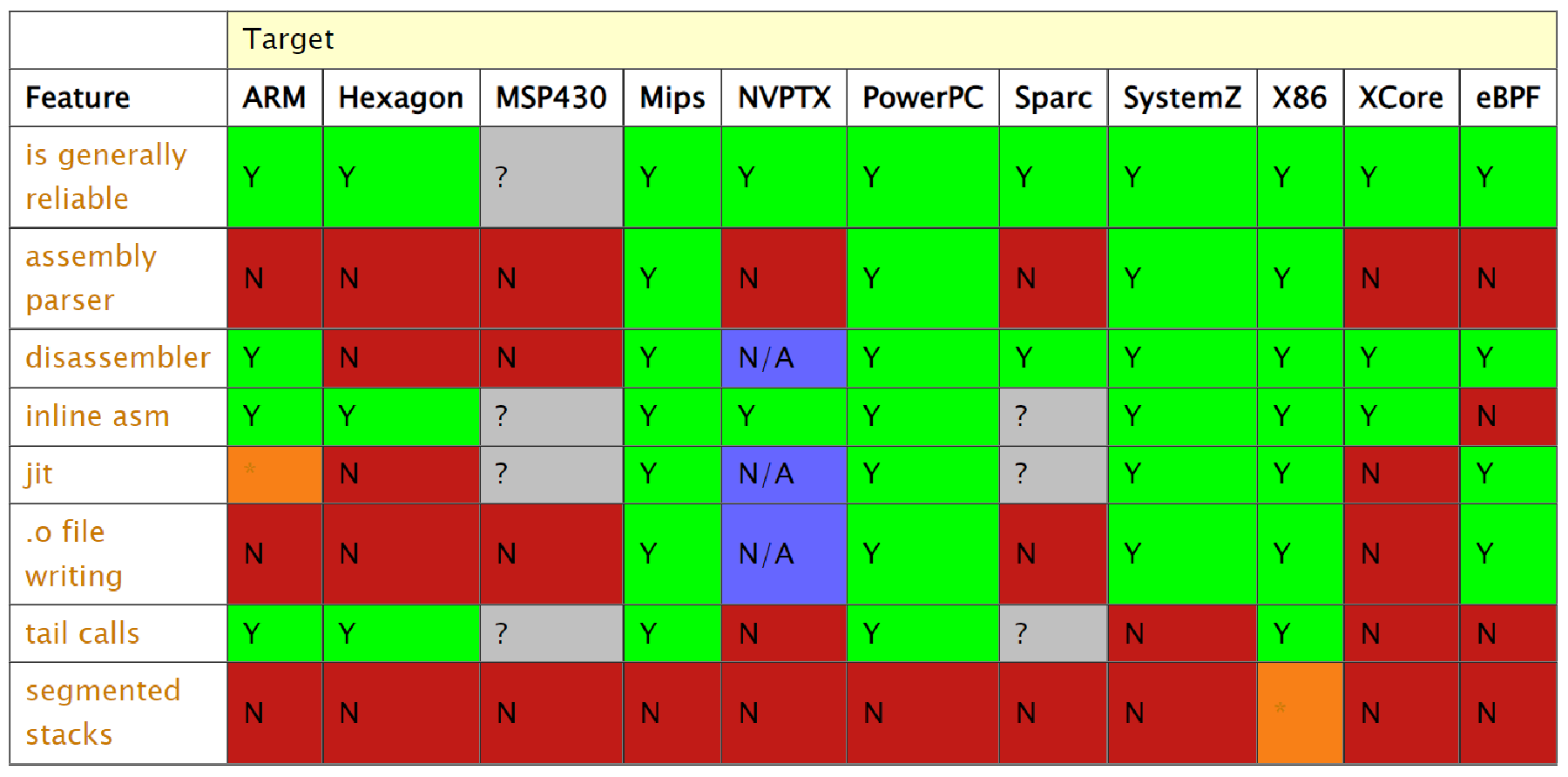

Now we can finally emit the optimized machine code, in whatever format the user desires.

Some targets support writing .o files directly, for others assembly will be written and assembled into an .o file as an intermediate step.

Note that to be able to run this file, we also need to link it, which Clang can do for you as well.

(Not Clang itself, Clang will just call a linker.)

As an example function, take this piece of code which will just copy over 16 integers from s to d.

void copy_16(int *d, int *s) {

for (int i = 0; i < 16; i=i+1) {

d[i] = s[i];

}

}

When we execute this, we basically do:

i := 0,

check:

is i < 16? if no goto end

d[i] = s[i]

i++

goto check

end:

return

So we’ll check 16 times if i < 16 and we’ll increment i 16 times, which is quite a bit of overhead, given that we know we want exactly 16 iterations.

Clang/LLVM will use loop unrolling to transform it into this:

void copy_16(int *d, int *s) {

d[0] = s[0];

d[1] = s[1];

d[2] = s[2];

// ...

}

So basically we just repeat the loop body 16 times and save the overhead.

Even if we don’t have a fixed upper bound for the loop, LLVM can still do something about it.

In this example we do the same thing but iterate up to n, which is a parameter, so not known at compile time.

void copy_n(int *d, int *s, int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i=i+1) {

d[i] = s[i];

}

}

Many CPUs have instructions that allow to copy over a lot more bytes at once, which is faster than only copying 4 bytes at once. So the compiler will try to use those instructions for the bulk of the copying and do the rest one-by-one again. That’s called vectorization.

void copy_n(int *d, int *s, int n) {

int i = 0;

for (; i < n-127; i=i+128) {

// copy 128 bytes at once

}

for (; i < n; i=i+1) {

d[i] = s[i];

}

}

In this example, we have a mixture of the above.

There’s copy_n, which still takes the upper loop limit as a parameter, and it is used in copy_16_v2, which unconditionally calls copy_n with n=16.

void copy_n(int *d, int *s, int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i=i+1) {

d[i] = s[i];

}

}

void copy_16_v2(int *d, int *s) {

copy_n(d, s, 16);

}

The compiler will now basically copy and paste the implementation of copy_n into the other function, which is called function inlining.

Then it can deduce that the for loop limit is 16, so it’ll make use of loop unrolling again.

void copy_16_v2(int *d, int *s) {

d[0] = s[0];

d[1] = s[1];

d[2] = s[2];

// ...

}

- [Ray Toal, Intro to Compilers] Toal, R. Intro to Compilers. https://www.cs.cornell.edu/~asampson/blog/llvm.html

- [Finkel, 2017] Finkel, H. and Horváth, G. (2017). Code Transformation and analysis using Clang and LLVM. https://llvm.org/devmtg/2017-06/2-Hal-Finkel-LLVM-2017.pdf

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/6319086/are-gcc-and-clang-parsers-really-handwritten

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/11510792/is-the-semantic-analysis-step-in-clang-an-essential-part-of-the-compiler

- https://cppdepend.com/blog/?p=321

- https://llvm.org/docs/CodeGenerator.html#legalize-operations

- https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2013/02/25/a-deeper-look-into-the-llvm-code-generator-part-1

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/845355/do-programming-language-compilers-first-translate-to-assembly-or-directly-to-mac

- https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2012/11/24/life-of-an-instruction-in-llvm/

- https://llvm.org/docs/CodeGenerator.html#target-feature-matrix

- https://blog.regehr.org/archives/1603

- https://github.com/llvm/llvm-project/blob/7175886a0f612aded1430ae240ca7ffd53d260dd/llvm/lib/Passes/PassBuilderPipelines.cpp#L717

- https://clang.llvm.org/docs/CommandGuide/clang.html

-

Some compilers translate into machine code directly (LLVM, mostly), other translate into assembly and use an assembler to compile it into machine code (GCC). ↩︎

-

Not necessarily, there’s something called Function Multiversioning, but that’s not automatic. ↩︎

-

Profile guided optimization might help in that case, though. ↩︎

-

There’s one other type of edge called

glue, that’ll make the instructions stick together through scheduling (see https://stackoverflow.com/questions/33005061/what-are-glue-and-chain-dependencies-in-an-llvm-dag). ↩︎ -

This mapping is not entirely static. Target-specific interfaces are used to map things like returns, calls, varargs, etc. (see https://llvm.org/docs/CodeGenerator.html#initial-selectiondag-construction). ↩︎